Common Misconceptions about Socratic Seminars and How to Use Them Effectively

January 1, 2018

I’ve talked to a lot of teachers about using Socratic seminars in class, a lesson format in which students take the lead in class conversation and the teacher mostly sits out. In my experience, teachers have a lot of different reactions to Socratic seminars. Some teachers love them and use them on a weekly basis, because they want to let students share their opinions and explore their argumentative skills. Other teachers dread them and struggle to feel that seminars are a worthwhile tool, because getting kids to participate can be a stressful battle. When I was first introduced to Socratic seminars, I hadn’t had any prior experience, and ended up learning a lot on the fly. Since then, I’ve adapted my method for using Socratic seminars to address different common challenges that arise with this lesson format, in order to make these discussions impactful and worthwhile. Ultimately, I’ve come to love using Socratic seminars, because they’re a great way to hear what all your students are thinking, to get them to express their opinions, and practice argumentative skills outside of just reading.

What is a Socratic seminar? A Socratic seminar, sometimes just called a seminar, is a discussion format for students to use to discuss a controversial or complex issue. In a seminar, desks are set up in two concentric circles and the class is split in half. One half sits in the center circle and one in the outer. The inner circle is the “active” discussion, while the outer circle is the “observer” group (the outer circle can have a range of different jobs depending on how you want to conduct your seminar). About halfway through class, you can switch the inner and outer circles, so that each group has a chance to discuss the issue at hand. (See FacingHistory or the TeachingChannel, or do a quick Google search for “Socratic seminar” for a wealth of resources that discuss seminars in greater detail).

How do you set up a seminar? You need three things to set up a successful seminar: a prompt text (or texts) and question; a preparation sheet; and clear expectations.

- The prompt: Teachers tend to be split on whether seminars should be based on a single text, or if they can be about multiple texts. As long as students have enough to base their arguments on, it won’t matter which one you choose. However, writing the question is key! Avoid questions that are very closely tied to content-specific topics, because these can be hard, especially for younger students. Ones that have universal bearing or application are easier. For example, instead of asking, “Did the Roman Empire make the right decision when they chose to convert to Christianity?” try, “Is it better for a civilization to allow diverse beliefs, or to encourage assimilation to a single, state-endorsed religion?” Paired with stimulus texts related to the topic students are discussing, the second question will help students apply their historical knowledge to present-day issues--which creates the liveliest kind of seminar.

- The prep sheet: Have your students fill out a preparation sheet before they come to class on the day of the seminar. The prep sheet has space for three things: an initial answer to the prompt question; a collection of evidence from our reading(s) that supports their answer; and a space for them to draft questions they want to ask their peers during the seminar. The first time you conduct a seminar, expect to spend more than one class period helping students prepare. However, once they’re familiar with the structure, they’ll quickly become more proficient.

- Clear expectations: Make sure you give your students the rubric for the seminar before having the discussion. Pick a few things you want kids to focus on in that rubric. On my rubric, students who encourage their peers to speak up can earn extra points, and students who “hog” the conversation can lose points. To avoid potential conflicts, make it clear that seminars are not debates--seminars are discussions in which you listen to your peers and respond respectfully, and they aren’t about winning or losing. If you have students who have no experience with seminars, you can coach them in how to respond to their peers, such as stating if they agree or disagree with the previous speaker before contributing their own point.

How do you make sure students participate? Many teachers shy away from seminars because they don’t like making shy students participate. However, I’ve done a lot of seminars, and my shy students always talk--eventually. They don’t always like it, but they will participate. There are a couple of ways to ensure this: Don’t allow students to opt out of the seminar (unless they are allowed special accommodations). If a student asks about an alternative assignment, tell them that there isn’t one and that everyone is expected to participate. If a student decides to skip class the day of the seminar, they have to come back in to do a make-up seminar in order to earn any credit for the assignment.

Second, try to encourage students to actually attend class on seminar days by providing a scaffold. Encourage them to talk to you if they’re feeling really nervous. If they do, let them know that they only have to participate once to earn full credit. Additionally, have them choose between a couple of options: they can go first, just read their answer to the prompt from the prep sheet, and be done. They still need to sit in the circle and listen, but they won’t be expected to jump into the conversation later. The other option is that they can have a “buddy,” another student in the seminar who is more confident, who will invite them into the conversation after they’ve spoken.

For particularly shy students, follow every Socratic seminar--whether they were able to participate or not--with a lot of positive feedback and encouragement. Ultimately, students usually try not to participate because they lack confidence, and building this confidence in them over time is the best way to make them feel better about participating.

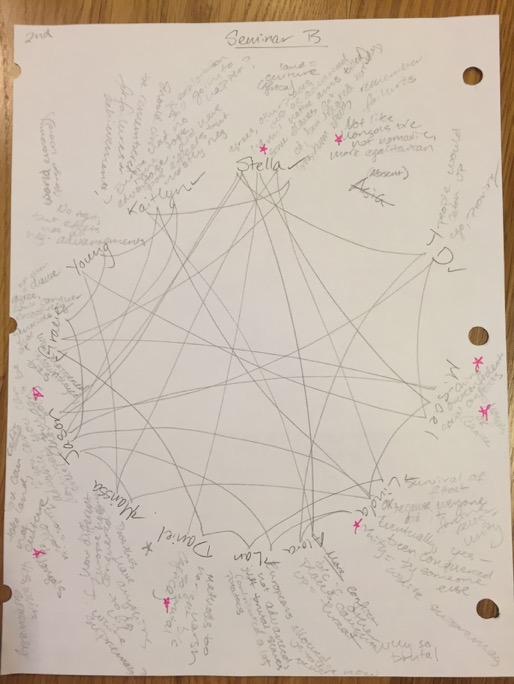

How do you grade a seminar? The last thing that scares teachers away from seminars is how to grade them. In a discussion of fifteen people, how do you keep track of what’s going on? Start by having a small set of criteria to look for (and include these criteria on your rubric!): number of contributions, whether or not the student contributed positively to the flow of the conversation, and whether or not they used effective evidence to support their points. Second, while students are discussing, sit on the outside of the circle and keep a map of the discussion that looks (at the end of of the seminar) like this:

Student names are written in a circle, and as the discussion moves from one student to the next, draw a line that connects the first speaker to the person that follows. At the end of the discussion, you can count how many times a particular student speaks by counting the “points” of these lines under each name. When the student speaks, take brief notes near the name to show what the student talked about. You can use a different colored pen to make a star every time a student uses a specific and appropriate piece of evidence. After the seminar, it’s pretty easy to look at this sheet and the student’s prep sheet to place them on the rubric.

Student names are written in a circle, and as the discussion moves from one student to the next, draw a line that connects the first speaker to the person that follows. At the end of the discussion, you can count how many times a particular student speaks by counting the “points” of these lines under each name. When the student speaks, take brief notes near the name to show what the student talked about. You can use a different colored pen to make a star every time a student uses a specific and appropriate piece of evidence. After the seminar, it’s pretty easy to look at this sheet and the student’s prep sheet to place them on the rubric.

Socratic seminars can be a powerful tool--and I encourage you to try them!

Check out the related blog entry: Ways to Include Student Voice in Your Teaching

Article by Alison McCartan, a regular contributor to The Heritage Institute's Blog, What Works: Teaching at Its Best.

Article by Alison McCartan, a regular contributor to The Heritage Institute's Blog, What Works: Teaching at Its Best.

Alison McCartan is a high school teacher in the South Puget Sound region of Washington State. She has taught English and history in high schools across the country, and when she's not orchestrating re-enactments of the Industrial Revolution in class, she can usually be found with a cup of tea, her cat, and a book.