The Future of Education

January 18, 2023

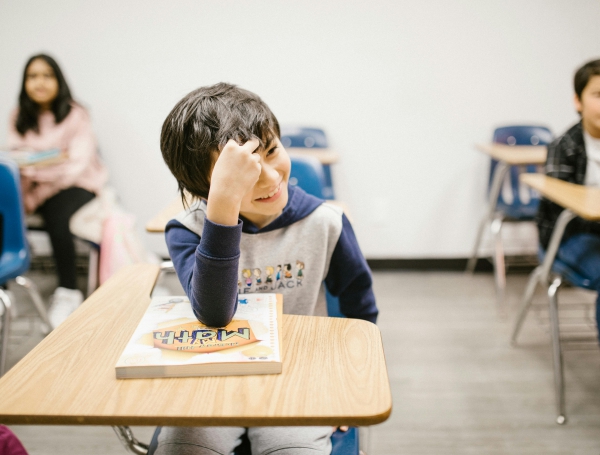

I can remember the exact moment when I saw the future of education. It was around 2005, and I was teaching eighth-grade English in a rural school in Pennsylvania. We were reading books that included White Fang, Julie of the Wolves, and The Call of the Wild. We had a classroom set of laptops, and for one assignment, students were researching animals that were the books they had chosen. A student found a video of a grizzly bear, and a half dozen of us huddled around his computer to watch what he found. I don’t remember the details of the video. What has remained with me all of these years was the sense that education was shifting. As we were watching the video, I looked away from the screen and at the students who were all leaning in, watching the video. I saw engagement. I saw all of us being transported, not only to a place with grizzlies but into the books we were reading. And at that moment, it hit me. This would be the future of education. I didn’t know exactly how that future would unfold, but I could see the impact technology would have on it. It was exciting.

Since that moment, we’ve come to rely on smartphones, Chromebooks, digital textbooks, interactive whiteboards, Google Workspace, Zoom, learning management systems, and countless apps. While teacher goals have not changed–engagement and skill development–these tools have shifted how classrooms can be organized. It’s easier for teachers to differentiate, flip classrooms, and create self-paced learning. I saw the power of this a few years ago when I created two self-paced units for English 8 using Canvas. One unit was about the history of English, and the other unit was an introduction to public speaking. For each unit, I created short video lessons and independent and partnered activities. Students had to complete assignments in order and pass short, repeatable quizzes to demonstrate a basic understanding.

During class, I moved around the room, checking in with students. I was pleasantly surprised–shocked, actually–by the final test results. Never had scores been so high, which I attributed to every student having to engage in the activities and not move forward until they could show they knew the material. Later in the year, I used the same structure with the public speaking unit. The self-paced lessons covered how to deal with stage fright, speech structure, effective gestures, and evaluating sample speeches. My first period that year was a co-taught class with a special education teacher. The class had both regular education and special education students. After the first two or three speeches, I looked across the room at my co-teacher. We had worked together for several years and never had the speeches, especially from the class that often struggled, been so polished.

A few months ago, I was consulting with a local wilderness first aid training company about the viability of making their courses hybrid. Both men are retired from the military, but one is particularly distrustful of technology in education. His concerns center on cheating and watering down the curriculum. While I acknowledged that some of the training they offer would be better in person (and every teacher should see technology as a possible tool to use but not the only tool that applies to all situations), I pointed to the powerful results in the self-paced units I’ve created. Embedded in his argument against change is the suggestion that the way we’ve always taught doesn’t have its own problems. That’s more of a choosing the devil-you-know response. In traditional lecture lessons, it’s too easy for students to disengage and look like they’re paying attention. The instructor typically doesn’t find out if the student understood the material until the unit exam, and if most of the class passed, the whole class is moving on. Self-paced learning allows students to rewatch videos, retry quizzes, and access additional lessons and content. Students must take more responsibility for their learning, reflecting on where they struggle to move forward. Because the teacher has put their lessons online, often in videos, during class, the teacher is free to work with students one-on-one or pull small groups together for other activities or lessons. And students can access lessons anytime, which helps with absences or those who want more time to work through the ideas or assignments. This is a much better use of time for both the students and the teacher, who no longer has to worry about creating a lesson that moves all twenty-some students together through the material.

I haven’t had any other epiphanies about the future of education like I did watching grizzly bears. But what I have learned from the last twenty years is to embrace innovation and to be curious about what new tools can offer. I don’t overwhelm myself by trying to learn about every new app. Instead, when I hear about a new tool, I consider its applications. Maybe I’ll use it. Maybe I’ll forget about it. Sometimes the lessons I try are duds, but the experience still teaches me something. And when the lesson works, I am only adding to the tools at my disposal to engage students and develop their skills.

This guest article was written by Catharine

This guest article was written by Catharine

Carbaught while taking the online continuing

education course Google Jamboard Basics

by THI instructor Rachelle Mulder.